The Secret of The Secret of Kells

Review by Oliver Gifford

Last Tuesday evening found my lovely wife and I engaging in another round of I-don’t-know-what-would-you-like-to-do. So, we pulled out one of our failsafe entertainment options – the Laurelhurst Theater – to break the deadlock. It’s a failsafe option, because $10 at the Laurelhurst will get you a movie, a slice of pizza, and a pint of microbrew.

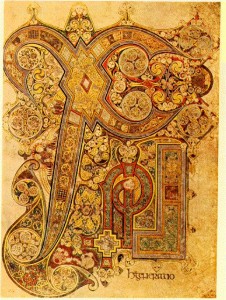

The animated feature we settled on, The Secret of Kells, promised a plot revolving around manuscript illumination. We settled on it mainly because a novice calligrapher/illuminator such as my own self couldn’t resist looking very interested when my wife read the plot summary, and because my wife can’t resist indulging me when I look interested.

As the movie started, I felt a sense of relief to be watching an animated film that isn’t CGI. Don’t get me wrong, Pixar films are gorgeous. But sometimes the perfect textures and flawless three-dimensional perspective gets almost a little inhuman. The two-dimensional, stylized animation of The Secret of Kells feels refreshingly warm, clearly influenced by the marginalia of the illuminated texts that form the central motif of the film.

But something else really caught my attention. A grin slowly spread across my face as I began to realize that the writers had a more-than-superficial acquaintance with the Jungian individuation process.

Without further ado, here is an analysis of the Jungian, alchemical symbolism present in The Secret of the Kells. As of the writing of this article, the film is still playing at the Laurelhurst, but not for very long! So get down there and watch it, then get back here and read this. And then maybe you’ll want to watch it again on DVD, with your new perspective.

The Secret of The Secret of Kells

The Secret of The Secret of Kells

(Spoilers ahead!)

The main character is a young boy, Brendan, who lives in a ninth-century village that is dominated by a solitary tower, the Abbey of Kells. In the image below, we see the tower workroom of Brendan’s uncle and guardian, Abbot Cellach. The center of the room is dominated by a diagram of the village and its tower. The mandalic nature of the image is unmistakable.

The illustration to the right is from one of Jung’s presentations on mandala symbolism. Mandalas have long been used in Eastern sacred art to represent the metaphysical cosmos. But Jung discovered that people who were in the midst of personal transformation often spontaneously drew mandalas, unaware of their import. These mandalas are filled with hidden clues about the state of a person’s consciousness. Jung used his knowledge of the symbolism to assist his patients on their path to metaphysical wholeness, a process he called individuation.

The illustration to the right is from one of Jung’s presentations on mandala symbolism. Mandalas have long been used in Eastern sacred art to represent the metaphysical cosmos. But Jung discovered that people who were in the midst of personal transformation often spontaneously drew mandalas, unaware of their import. These mandalas are filled with hidden clues about the state of a person’s consciousness. Jung used his knowledge of the symbolism to assist his patients on their path to metaphysical wholeness, a process he called individuation.

Abbot Cellach’s Repressed Nature

Abbot Cellach is obsessed with building a wall around the Abbey before Viking hordes can reach the city. But the wall, the forest, and the dangers outside the village are really projections of Abbot Cellach’s inner conflict. It doesn’t take long for us to observe his unbalanced character. His mindset is rigid and materialistic, rejecting anything playful, spiritual, or mystical.

Jung calls the archetypal masculine and feminine points-of-view the animus and the anima, respectively. Abbot Cellach has embraced his animus – his rational, practical side – and has repressed his anima – his intuitive, emotional side. This tendency to embrace and reject aspects of ourselves is normal, but it also stands in the way of our individual progress.

Each of us has a conscious and unconscious side. Every time we define ourselves as one thing, we imply that we are not its opposite. For example, we might say that we are cheerful, implying that we are not gloomy. In the big picture, these definitions are not completely true. We are not our moods, and even a person who is often cheerful is capable of being gloomy sometimes. Wholeness is about moving beyond these self-imposed limitations, and learning to choose from a range of behaviors consciously, instead of being powerless to resist the contradictory whims of our conflicted nature.

A town surrounded by a forest is a perfect symbol for the conscious and the unconscious. The town is familiar and safe. The forest, the unconscious side, is filled with the rejected aspects of our nature. The forest is full of danger, but it must be explored if we are to become whole.

The Arrival of Brother Aiden of Iona

The Arrival of Brother Aiden of Iona

Twelve-year-old Brendan is fascinated with illumination. While illumination here refers to the decorations found in ancient manuscripts, the hinted reference to illumination, in the sense of enlightenment, is not lost on us. One day, Brendan listens to the Abbey scribes talk about a famed illuminator, Brother Aiden of Iona, who has been working on a manuscript of unparalleled beauty. Before long, Brother Aiden (who bears a striking resemblance to Willie Nelson!) arrives at the Abbey with the manuscript, having fled from Iona after it was attacked by Vikings.

Brendan is desperate to see this manuscript, and Aiden shows it to him. Soon, brother Aiden is sending Brendan on a mission into the forest to find some berries to make an emerald green ink.

The archetype of the relationship between the wise old man and the young student is familiar to most of us. One of the most well-known examples is Merlin and King Arthur. Jung refers to the mentor as the “wise old man” archetype. In our dreams, when the wise old man makes his appearance, his nature is often ambiguous. He may ask us to go on strange quests, put a challenge in our path, or instigate problems for us.

What the wise old man really signifies is the self-reflective part of us that forces us to grow, usually by triggering the resolution of internal conflict. Often, conflict gets worse or comes to a head before it is resolved. It can be unpleasant. The difficulties are not the wise old man’s fault, though. The latent conflicts were a pre-existing condition, and we sometimes cannot accept the need to make a choice until he comes along and forces our hand.

When Brother Aiden sends Brendan on the mission into the forest, he is exposing him to the dangers of the forest. He is also sending him down a path of opposition to his uncle by encouraging him to ignore the uncle’s rules, which forbid Brendan from going outside the city walls. But Brendan has been pulled by the lure of illumination since before Aiden’s arrival, and eventual conflict with Abbot Cellach is inevitable.

The Forest

The Forest

Brendan has been taught to fear the forest, but the desire to be involved in illuminating manuscripts helps him overcome his fear. So he sets out on his quest. In the forest, though, he comes face-to-face with the dangers that lurk the unconscious, and is forever changed.

Initially, Brendan finds the freedom of the forest beautiful and exhilarating, but soon he gets lost and panics. He is chased by wolves.

As we already discussed, the forest represents the unconscious. As a symbol of the unconscious, the forest provokes ambiguous sentiments in us. On one level, the beauty of nature hearkens back to our Edenic origins, when we lived in a state of animal bliss, unperturbed by the conflict that came with the dawning of human consciousness. But on another level, we fear being overwhelmed by our unconscious, and reverting to a pre-civilized state. Hence, wandering alone in a forest can sometimes induce an irrational panic.

Brendan is saved by a shape-shifting fairy named Aisling. One moment, she takes the form of a wolf, chasing off the other wolves; in the next instant she is a white-haired girl, calling him a trespasser and ordering him to leave her forest. She doesn’t understand his logical world, or even the concept of an illuminated manuscript. But she sees Brendan’s sincerity and understands how important his mission is to him, and her initial mistrust wears off. Soon she decides to assist in his mission of finding the berries.

Brendan is saved by a shape-shifting fairy named Aisling. One moment, she takes the form of a wolf, chasing off the other wolves; in the next instant she is a white-haired girl, calling him a trespasser and ordering him to leave her forest. She doesn’t understand his logical world, or even the concept of an illuminated manuscript. But she sees Brendan’s sincerity and understands how important his mission is to him, and her initial mistrust wears off. Soon she decides to assist in his mission of finding the berries.

Brendan is just as uneducated about her world. He lacks her intuition, energy, and magical abilities. But she helps him, and he can’t help but learn from her. It’s not hard to see that these two are complementary opposites.

Aisling the fairy is Brendan’s anima, his female soul. We each have an animus and anima – a masculine, logical side; and a feminine, intuitive side. While they have very different traits that make them initially very wary of each other, they are really both part of one being. With the right mission – a task that truly inspires us – these two sides find the motivation to pool their resources and work together.

Brendan and Aisling find the berries, and Brendan brings them to Brother Aiden. In return, Brother Aiden teaches him how to make ink. Soon, Brother Aiden begins teaching Brendan how to illuminate. It becomes clear that this is Brendan’s calling, his true will. But following it leads to conflict with his uncle. Soon, Abbot Cellach locks him in the tower to prevent him from wandering into the forest again, and Brendan needs Aisling’s help in order to escape and continue his important work on the manuscript.

Sometimes, our conscious side reminds us of important concerns, and assists in our self-preservation. But our conscious side can quickly overstep its bounds, and begin to sabotage or interfere with our work. We can’t forego our legitimate needs while we pursue our soul’s wishes exclusively, but we also can’t let practical concerns hold our dreams hostage.

Following our true will brings its own challenges. For example, as Brother Aiden and Brendan prepare to work on the manuscript one day, Brother Aiden discovers that he has lost his crystal, a quasi-mystical tool that he uses to illuminate. Without it, they cannot continue working. Brendan soon realizes that the crystal is the “eye” of Crom Cruach, a dark and dangerous creature residing in the darkest part of the forest. Brendan knows that he must face Crom Cruach if he wishes to help Brother Aiden finish the manuscript.

Following our true will brings its own challenges. For example, as Brother Aiden and Brendan prepare to work on the manuscript one day, Brother Aiden discovers that he has lost his crystal, a quasi-mystical tool that he uses to illuminate. Without it, they cannot continue working. Brendan soon realizes that the crystal is the “eye” of Crom Cruach, a dark and dangerous creature residing in the darkest part of the forest. Brendan knows that he must face Crom Cruach if he wishes to help Brother Aiden finish the manuscript.

The crystal is synonymous with the pearl of high price, the philosopher’s stone, and many other hidden treasures that heroes in fairy tales are called upon to obtain, in spite of great peril. It represents the heights of human consciousness: the reborn, integrated Self.

Brendan returns to the forest to retrieve the eye. Aisling the fairy is terrified of Crom Cruach, but she helps him anyway because she understands that the mission is so important. They make their way to the darkest part of the forest, where Brendan finds Crom Cruach, an enormous black serpent. This is the shadow.

Brendan returns to the forest to retrieve the eye. Aisling the fairy is terrified of Crom Cruach, but she helps him anyway because she understands that the mission is so important. They make their way to the darkest part of the forest, where Brendan finds Crom Cruach, an enormous black serpent. This is the shadow.

To the right is the mandala that I posted earlier in the essay. Notice that there is a black serpent lurking in the forest of unconsciousness in the outer ring of the mandala. In our dreams, the shadow often takes the form of a snake, perhaps as a genetic vestige of the practical dangers that snakes posed our ancestors. The shadow is an archetype that serves as a vessel for our rejected traits. Everything we fear, every unpleasant truth about ourselves, everything we hate, is found in the shadow.

The shadow is the source of real dangers, in the form of the influence it can have in our lives. We can project our shadow, and accuse others of every secret evil that lurks in our hearts. Or we can fall under the control of our shadow side, and act out our darkest desires without giving a thought to the consequences,  like Mr. Hyde, when Dr. Jekyll loses control of his shadow.

like Mr. Hyde, when Dr. Jekyll loses control of his shadow.

But these dangers exist whether we confront our shadow or not. And we must confront it, if we want to become whole. So Brendan fights Crom Cruach. Eventually, Brendan prevails, and is able to contain him. In the process Crom Cruach is transformed, and begins swallowing his own tail. He is now an Ouroboros.

Jung had some very interesting things to say about the symbolism of the Ouroboros:

“The alchemists, who in their own way knew more about the nature of the individuation process than we moderns do, expressed this paradox through the symbol of the Ouroboros, the snake that eats its own tail. The Ouroboros has been said to have a meaning of infinity or wholeness. In the age-old image of the Ouroboros lies the thought of devouring oneself and turning oneself into a circulatory process, for it was clear to the more astute alchemists that the prima materia of the art was man himself. The Ouroboros is a dramatic symbol for the integration and assimilation of the opposite, i.e. of the shadow. This ‘feed-back’ process is at the same time a symbol of immortality, since it is said of the Ouroboros that he slays himself and brings himself to life, fertilizes himself and gives birth to himself. He symbolizes the One, who proceeds from the clash of opposites, and he therefore constitutes the secret of the prima materia which […] unquestionably stems from man’s unconscious.”

“The alchemists, who in their own way knew more about the nature of the individuation process than we moderns do, expressed this paradox through the symbol of the Ouroboros, the snake that eats its own tail. The Ouroboros has been said to have a meaning of infinity or wholeness. In the age-old image of the Ouroboros lies the thought of devouring oneself and turning oneself into a circulatory process, for it was clear to the more astute alchemists that the prima materia of the art was man himself. The Ouroboros is a dramatic symbol for the integration and assimilation of the opposite, i.e. of the shadow. This ‘feed-back’ process is at the same time a symbol of immortality, since it is said of the Ouroboros that he slays himself and brings himself to life, fertilizes himself and gives birth to himself. He symbolizes the One, who proceeds from the clash of opposites, and he therefore constitutes the secret of the prima materia which […] unquestionably stems from man’s unconscious.”

By neutralizing Crom Cruach, Brendan is able to reap the rewards of individuation. He is able to retrieve the serpent’s eye, and return to the Abbey to begin working on the manuscript with Brother Aiden. What was formerly an aspect of Brendan’s mortal enemy is now the tool that helps Brendan continue his life’s work.

By neutralizing Crom Cruach, Brendan is able to reap the rewards of individuation. He is able to retrieve the serpent’s eye, and return to the Abbey to begin working on the manuscript with Brother Aiden. What was formerly an aspect of Brendan’s mortal enemy is now the tool that helps Brendan continue his life’s work.

If we can find the value that the shadow guards, we can transform the prima materia – our base nature – into the philosopher’s stone – the whole, individuated Self. Jung found this process hinted at in many other sources, from fairy tales to religious allegory.

Recall, for example, the gospel of Luke, where Jesus quotes Isaiah, saying “The stone that the builders rejected has now become the cornerstone.” Our new perspective breathes a very different meaning into these words.

Soon after Brendan’s confrontation with Crom Cruach, Abbot Cellach’s fears come true, and Viking hordes arrive, break through the walls, and pillage the Abbey. The Abbot Cellach is wounded. This is a powerful reminder that the unconscious cannot be repressed indefinitely. Eventually it breaks through, and when it does, it unleashes chaos. Abbot Cellach becomes the fisher king, the wounded king archetype, whose imbalance has brought suffering to himself and his kingdom. In repressing the unconscious, he has rejected the source of vitality, and cannot be whole.

Soon after Brendan’s confrontation with Crom Cruach, Abbot Cellach’s fears come true, and Viking hordes arrive, break through the walls, and pillage the Abbey. The Abbot Cellach is wounded. This is a powerful reminder that the unconscious cannot be repressed indefinitely. Eventually it breaks through, and when it does, it unleashes chaos. Abbot Cellach becomes the fisher king, the wounded king archetype, whose imbalance has brought suffering to himself and his kingdom. In repressing the unconscious, he has rejected the source of vitality, and cannot be whole.

On another level though, the breaching of the Abbey walls and the wounding of Abbot Cellach is a direct result of Brendan’s fight with Crom Cruach. Integrating the shadow unseats the ego from its position as the king of our existence. Abbot Cellach’s control over Brendan’s fate is ended.

Confronting the shadow does not mean literal death, but it is a death for many of our illusions about who we are. It is unpleasant. It brings painful memories to the surface and forces us to face bitter truths about ourselves.

Brother Aiden and Brendan flee to the woods, where they reside and continue working on the manuscript. Years later, Brendan, now an adult, returns to the Abbey, where the aged Abbot Cellach apologizes, having grown to realize the error of his ways. Seeing the amazing illumination in Brendan’s complete manuscript, his sense of magic is restored.

Brother Aiden and Brendan flee to the woods, where they reside and continue working on the manuscript. Years later, Brendan, now an adult, returns to the Abbey, where the aged Abbot Cellach apologizes, having grown to realize the error of his ways. Seeing the amazing illumination in Brendan’s complete manuscript, his sense of magic is restored.

This reminds us that every effort we make toward consciousness has a huge return on investment. Our ego will recover from the wounds caused by the sometimes traumatic process of becoming whole. Individuation may create temporary issues, but is ultimately a source of healing to our entire being, including the ego. As long as we stick to this path, we can’t go wrong.

So how do we know we’re on the right path? Real hurt can come from those acting with the best of intentions, after all. Abbot Cellach though he was acting in everyone’s best interests, but he was only hindering Brendan’s true will.

So how do we know we’re on the right path? Real hurt can come from those acting with the best of intentions, after all. Abbot Cellach though he was acting in everyone’s best interests, but he was only hindering Brendan’s true will.

Do what inspires you.The key is to examine our root motivation. Often, if we examine our motives, we will find that we are being pulled in opposite directions. We might be pulled between doing what we think we ought to do, and indulging our basic desires.

Try something different. Don’t let either side win. Avoid guilt-inspired dutifulness and temptation with equal resolve. Instead, find something that captures the attention of both your conscious and unconscious, your rational and emotional sides, and commit to that.

Do what inspires you.

Great article. A lot of information and understanding of it. I really want to see this movie now.

This is exactly what I was looking for! Thank YOU!!!

I knew there was something special about this movie. It just captured me the moment I saw it till the moment it ended. all the ideas seemed perfect to me. Thank you for this article! It has given me the reassurance I was looking for.

This is a great page and you have, so far, gotten as much of the symbolism or more than anyone else.

However…I think you completely missed some key themes.

Now, there is a great deal of nuance in this movie, like why Aiden keeps the book even after Cellach asks for it and could clearly take it by force. Also, things like the number of wolves with gnashing teeth that Pangur Ban passes through right before Aisling appears. Those things are easily missed. You missed some key themes in the movie overall.

Firstly, you completely passed over the extremely sexual symbolism in the relationship between Brendan and Aisling and what the ramifications of that mean for the rest of the movie. The opening shot of Brendan sitting and writing on a tablet placed just so in his lap and Aisling is looking at it and gently touching it. What do you think “one beetle recognizes another” means?

Also, your analysis of Crom Cruach is incomplete. The Ouroboros symbol is a good start but you don’t say WHY it must be that this illuminating device must come from this most horrifying monster. “Pagans and Crom worshippers” Cellach called his flock. Crom is not just a stand in for the devil though. He represents the primal force of nature, the will to life that brings death to all that oppose it. As the epitome of natural “evil” one could interpret Crom as the manifestation of SELF-ishness. The eye of Selfishness being of course the eye of self awareness once in Brendan’s hands.

The symbolism of the scene where Aisling lets Brendan out of his room in the tower is one of the most richly meaningful scenes in any movie I have ever seen. She knew that she was the ONLY one that could let him out, and she also knew the price she would pay for doing it, yet she did it anyway. My God I cried so much when I saw it. The meaning I saw was this: Man in his base reason will lock up his intuition for the sake of “security.” Only loving nature in the form of the “Other,” the love of someone else outside the walls of yourself, can truly set it free. It does this by a secret process that operates outside of and above base reason, and by the strength of that love the key to intuition may be retrieved from sleeping, thought-free mind.

However, this process has a price. According to other websites the translation of her song to Pangur Ban is “There is nothing but mist in this life/world, and we are alive for a very short time.” For Brendan to create the Great Work, she must pour her very self onto the page, be the ink from that he makes the Book. It is the sacrifice of nature, of the divine feminine, by that we may continue on our cycles of Life.

I apologize if I seem snobbish guys. This really is a wonderful description of the major themes in this beautiful, almost transcendental piece of art. Thank you very much.